1. Introduction

Modern day software development is spread more and more across national and international boundaries. Global software development (GSD) is now the need of the hour more than ever. One of the important concepts evolved in the past decade or so is the “Follow the sun” (FTS) software development.

It is a model in which work from one site is handed over to another, which is many time zones away (for example, U.S.A to India), in order for the work to be advanced while one team rests for the night. It is also known under different names such as 24 hour development or Round the clock development.

Figure 1: Follow the Sun approach follows a 24h task hand-off based approach to software development

Figure 1: Follow the Sun approach follows a 24h task hand-off based approach to software development

The major benefit is the development duration or the potential in reducing the time-to-market. Theoretically speaking, if ‘n’ sites are working on this scheme, their development speed could be increased dramatically by systematically organizing the work tasks sequentially on a daily basis and optimizing the coordination costs [1].

Although this seems like such an intuitive idea to work with, it is not practiced widely, misunderstood often and has had few documented industry success cases.

2. Background

To get a proper picture of the background on FTS, there is a need to understand a development pace and its associated concept of time to market, which are the main drivers of the development of FTS. Time to market is the amount of time it takes from the moment the product is conceived until the product is available for use or sale. This is very important especially for industries whose products become outdated in a very short time (e.g. mobile handsets, firmware, e-commerce systems, and innovative supply chain management).

Many factors influence the need to develop the products quickly such as avoiding contract creep, schedule slippages, budget overruns and other managerial reasons. To fulfil this need, most firms try various strategies such as working overtime, skipping steps and setting aggressive deadlines. These are reactive in nature. But these steps will add to the increase in cost due to burnout and fatigue [2]. Adding more man power to the project is not of much interest in software development, because of the wisdom gained long ago from the seminal Brooks’ law “adding manpower to a late software project makes it later” [3]. These difficulties prove that a systematic approach is needed in achieving a quick time-to-market strategy, which in turn leads to the Follow the Sun software development scheme.

3. Principles of FTS

In order to understand and use FTS, some key principles on which FTS is based are mentioned in this section.

- FTS is a global software development strategy.

- The main criteria to go for FTS is the reduction in the development time or time-to-market.

- Production sites involved in the software development are many time zones apart.

- There is only one site that owns the product at any point in time.

- Project handoffs are done on a daily basis at the end of each shift.

- The handoffs can be applied to any software development task.

The above principles allow FTS to be used in any knowledge work (not just software development). There are claims that FTS is being used at General Motors and at OfficeTiger [4] [5]. Some key assumptions in deriving the above principles are listed below:

- Each production site works during the day as a “subteam” and it needs within-site coordination.

- A subteam can consist of one or more members.

- A handoff from one site to the other can be occasionally empty due to public holidays or emergencies.

- There is a common product repository which allows each site to be in sync with their work at the end of each workday.

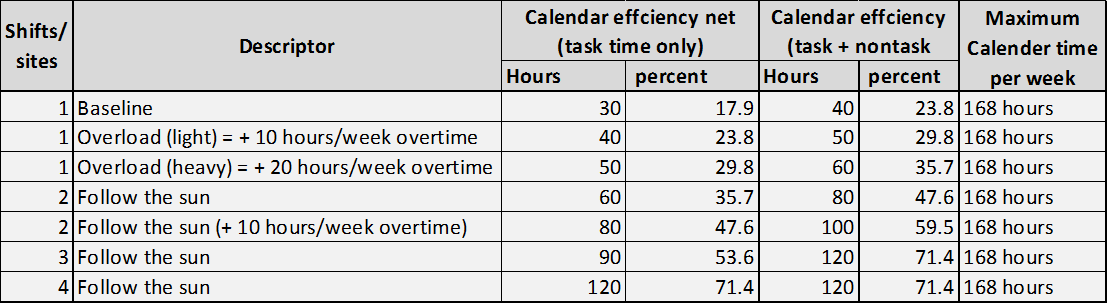

Follow the sun approach involves daily handoff of the work which suggests that there will be some reduction in the project duration. A detailed analysis needs to be done in order to understand the advantages to be gained in time. One such analysis is done using the “calendar” time [1] available for production. The term calendar efficiency helps in understanding the analysis further. It is defined as the percentage of all of the calendar time (e.g., 24 * 7 = 168 hours available per week) that is used productively for work, so, a 40-hour workweek utilizes 23.8 percent of the calendar workweek, showing that there is a lot of room for calendar efficiency improvement.

The table in Fig. 1 gives the relevant facts regarding various working schemes. For example, a baseline work week is 30 hours after taking into account non-task activities. Calendar efficiency can be increased in a simple way by working overtime (overload mode), but this only improves the efficiency by 6%. Heavy overload still improves the efficiency by just 12% but it is not an effective long term strategy due to employee burnout. This is where FTS potential gains a lot, as is evident in the bottom rows of the table. An optimal FTS configuration could raise the calendar efficiency as high as 71.4%.

Figure 2: Calendar Efficiency in different Working Modes [1]

Figure 2: Calendar Efficiency in different Working Modes [1]

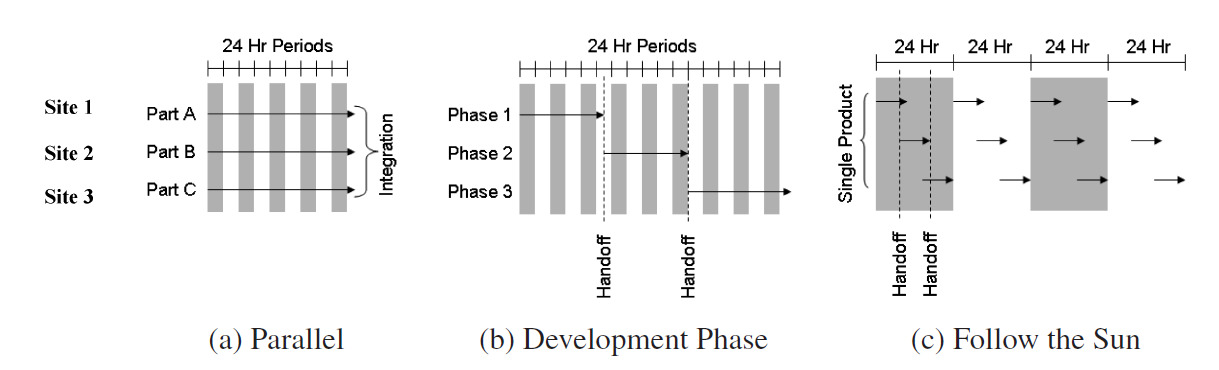

4. Traditional Software Development vs FTS

There are several major differences between traditional globally distributed software development and the FTS approach. In traditional software development, global teams are less dependent on one another and usually do not pass on the work (hand-off). Hand-offs are the central idea of the FTS approach. The efficiency of the number of hours per day spent on actual development is much higher in the FTS model when compared with traditional software development [1]. This is because work happens almost round the clock, compared to just eight hour efforts in traditional software workflow. This efficiency further increases with the number of locations and shifts.

At any given time only one team owns the product unlike other global configurations in which multiple locations can own different parts of the product. As illustrated in Fig. 2 traditional software development stresses on minimal job hand-offs, whereas FTS focusses on day-to day job hand-offs [1]. Because of its uncommon nature, FTS is also least practiced in the industry and has very few documented examples of success. When compared to traditional global software development, FTS workflow is more difficult to achieve.

Figure 3: Comparing FTS model with other global workflows [1]

Figure 3: Comparing FTS model with other global workflows [1]

Not All Global Workflows are FTS

Several workflows seem to be using the FTS model, but in reality this is not always the case. Based on the discussions in the Principles of FTS section which explains the minimum criteria for a work flow to be considered as a FTS approach, the following do not fit in this category [1]:

- Software development involving multiple global locations in different time zones is not always FTS if it does not satisfy all the criteria mentioned in the Principles of FTS section.

- Global business processes such as call centres or help desks are not counted under the FTS umbrella.

- Collocated multishift – locations where labour is cheap and software development happens round the clock in eight hour shifts does not fit in this category.

5. Agile and FTS

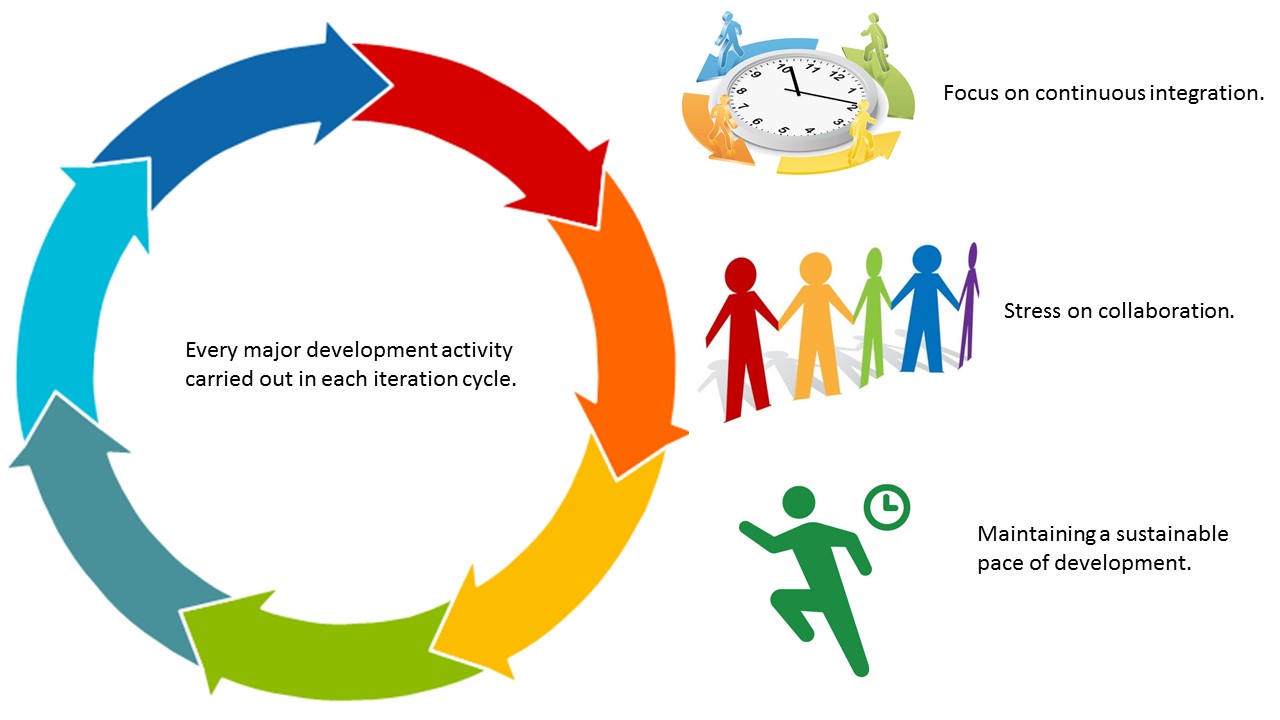

Agile software development practice consists of a set of principles which advocate continuous improvement, adaptive planning, early delivery and flexibility in responding to change. The various agile methodologies such as Scrum, Lean, Kanban, Extreme Programming (XP), DSDM etc., share much of the same characteristics and practices and are widely practiced in Globally Distributed Software Development. FTS is a special case of GSD which aims to achieve a 100% workday in software projects. As described by Carmel [1], the agile methodology is best suited for FTS.

5.1 Traditional Software Development Models and FTS

Linear sequential approaches such as the Waterfall model seem to be inefficient for the FTS approach. Carmel [6] argues that only the nature of some phases of the development cycle such as testing are well suited for FTS. As a result, the benefits of FTS tend to be concentrated around isolated phases rather than having an overall impact on the development cycle. Hence it is important to select a software development methodology which extends over the entire software development cycle and satisfies the special needs of daily hand-offs.

5.2 Agile - a perfect match for FTS

Agile has several characteristics which support FTS adoption [6]. In an Agile based methodology, all major development activities (design, code, test and integrate) are carried out in every iteration cycle. The iteration period lasts for a short time period (between two to four weeks). Agile places a lot of emphasis on continuous integration (using automation) encouraging every team to maintain an updated and testable version of the code which can be used by the next production site. This facilitates easy job hand-offs and fits nicely within the FTS model. Agile also provides an opportunity for every team to maintain a sustainable pace of development i.e. working only during daylight hours. Agile stresses on the importance of automated testing to reduce time. Collaboration between teams is very important in Agile, a trait which is also a characteristic of FTS model. Because of these reasons FTS is best suited for Agile. However, one slight difference is that Agile stresses on face to face communication, whereas in FTS inter-site communication between production sites is maintained at the bare minimum by using automated tools.

Figure 4: Agile is a perfect choice of software development methodology for FTS

Figure 4: Agile is a perfect choice of software development methodology for FTS

Others, such as Gupta [5], also make similar observations and propose that FTS is very well suited to support core agile practices. A research carried out by Yap [7], a globally distributed software project team (UK, USA, and Singapore), followed the FTS approach under the Extreme Programming (XP) model (an Agile methodology ). Initial handoffs mainly consisted of daily work summaries, which were later augmented by knowledge transfer activities. Though the teams faced initial setbacks due to cultural differences and technical glitches, by re-orienting their thinking they could successfully implement agile practices across all locations on a single working codebase.

6. Technology Tools and Infrastructure to support FTS

FTS approach has only a handful of documented cases of industrial success because of its nature. A part of this may be attributed to the availability of efficient tools and enabling technologies for implementing the FTS model. Software tools used for actual FTS implementation must include both managerial and technical aspects, to adapt to the changing requirements of the software development process.

Tools for estimating and planning schedules, allocation of project tasks, sprint management, progress tracking are essential utilities for front line managers. Mechanisms for transferring work in progress to the next site is the core idea of FTS. The process of hand offs must be smooth and conflict free. It must also ensure that all the required information and reports to continue the work are visible and easily accessible. The focus is on using automated tools which simplify the repetitive tasks. Some other day to day tasks enabled by software include – logging time spent by developers, issue tracking, real time reporting, code reviews, and documentation.

The effective utilization of code repositories and version control management systems is crucial to the success of the FTS approach. It is quite possible that hundreds of software developers and testers can be working on a project in cycles. Most of the current code repositories are cloud based and accessible across geographies. In this distributed model, the CIA [8] (the triad of Confidentiality, Integrity and Availability of service and data) assumes paramount importance. This infrastructure must always be available on demand and accessible. Tools to support data security and encryption such as VPN’s are also important. The ability of project management tools to integrate with development tools can help reduce the duration of project cycles in FTS.

Figure 5: Successful implementation of FTS depends on reliable software tools and utilities

Figure 5: Successful implementation of FTS depends on reliable software tools and utilities

Modes of communication in FTS approach may be asynchronous or synchronous. The geographically dispersed nature requires the use of software applications which facilitate tele-conferencing, VoIP calling, instant messaging etc. Knowledge transfer and sharing of project critical information with concerned parties is essential for smooth operation of the project. Formal systems such as discussion forums or internal Wiki sites may prove to be useful. If communication issues are not addressed they will create significant challenges in FTS adoption.

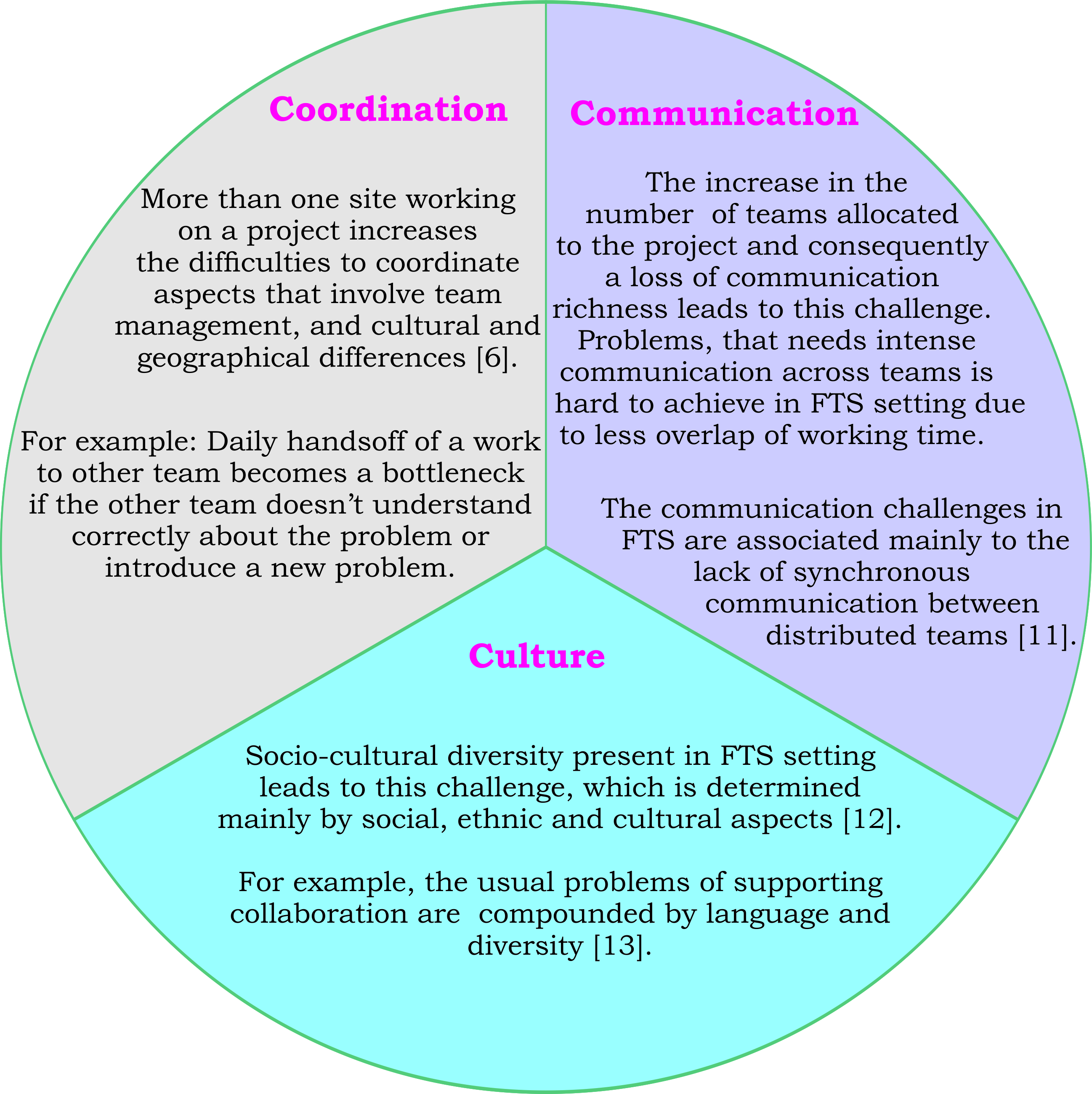

7. Applying the FTS Model in Practice

The FTS approach is based on the principle of handing-off unfinished work to the next location at the end of work day. To manage the workflow efficiently the principles shown in Fig. 5 are applied in practice.

Figure 6: Five essentials for applying the FTS model in practice

Figure 6: Five essentials for applying the FTS model in practice

8. Real World Examples of FTS

One of the ways to evaluate the efficiency of FTS is to compare the time taken to execute a project using traditional software development approaches vs FTS. Apart from the usual difficulties faced in globally distributed software development, FTS also has the additional challenges of managing daily job hand-offs. It is interesting to note that there have been very few documented cases of successful FTS application in the software industry.

Three important companies which documented their experience is summarized below.

-

IBM in 1990’s was probably one of the first companies to record the implementation of FTS in its software development teams globally [1]. This project involved five global teams distributed across five different countries. The initiative was unsuccessful, and the project was ultimately implemented using only the essential principles of global software development.

-

Treinen and Miller Frost [19] published a case documenting two cases of FTS implementation at IBM. The first one involved a software development project consisting of teams in the United States and Australia and met with high degree of success. The second case study involved three distinct projects with development sites in the United States and India, and met with drastic failure. Several reasons such as misinterpretation of specifications, multiple rework cycles, lack of proper coordination and communication between teams, time zone issues and cultural differences were attributed to the project’s failure.

-

Another documented case of FTS application was by Infosys [20] in 2005 where FTS was applied to small subsets of the project cycle. Infosys concluded that applicability of FTS was limited and highly specific to the nature of the task at hand. Cameron [13] highlights the example of FTS application at EDS (now a part of HP).

Case Studies:

Two case studies reported on the application of FTS in software development is elaborated below.

-

WDSGlobal case study: In 2004 a study conducted within the company of WDSGlobal reported the following list of what worked in FTS software development (when doing Extreme Programming) [7]:

* Daily handovers. * Face-to-face communication (video calls for handovers). * Shared common configuration. * Remote pairing, for "collaborating on ideas and sharing experiences, removing misunderstandings, and fostering shared memory between the pair and through them the teams". * Round-the-World Program, which means that each member of the team works at each region for four to six weeks (if possible), which means that a team member gains "a certain level of knowledge of the background and shared cultural values, and building trust with members in other regions". * Work together on features and issues. * Coaches had one-on-one meetings after daily handovers, all coaches had weekly meetings to discuss issues and once in a quarter all coaches physically met for two weeks to deal with more complicated issues and discuss long term planning. * Regular discussions about Extreme Programming.The study reported the following lessons that were learned:

* Balance teams, so that one team does not dominate the project. * Introduce "a set of rules and pre-defined processes" so that "all of the team members know exactly what to expect from each other". * The problem of introducing innovation. Ideal would be a consensus among the whole team, but this is very time consuming, due to different locations and time zones. * Allow some flexibility in different locations with respect to shared processes.The study involved teams from the USA, UK and Singapore. Although these regions share the English language, there were cultural differences, for example, “one culture has more emphasis on self-sufficiency; therefore they tend not to ask for help when problems come up. Another culture would not offer their help unless they were asked while the third considered that presenting the problem was a sufficient invitation for willing team members to jump in and help”.

-

FTS feasibility study: In 2013 there was a feasibility study of FTS in the industry [18]. The work involved a software project developed by teams in Mexico, India and Australia, which followed Scrum. There was a 30 and 60 minutes overlap between locations “to enable the daily handover of tasks”. The three teams consist of 2 micro-teams (composite persona [17]), with at least one person from each location. The result was that the project was completed in 5.5 weeks, while it was estimated to be completed in 6 weeks in non-FTS mode, so it reduced time.

Major lessons learned in the study that could improve FTS from their experience include:

* Templates and standard documents in the project * Coding standards * Screen sharing * A communication protocol * Tasks for the day for individuals * Handover template * Assign tasks to a composite persona ownerIt was also observed that hand-offs between different sites were especially difficult in the weekends. Since there is no overlap during the hand-off and the hand off happens, for example, via e-mail, instead of via the phone or other communication tool.

Based on these observations and the results presented in literature, it can be said that FTS approach is not widely used in practice because of its limitations and challenges.

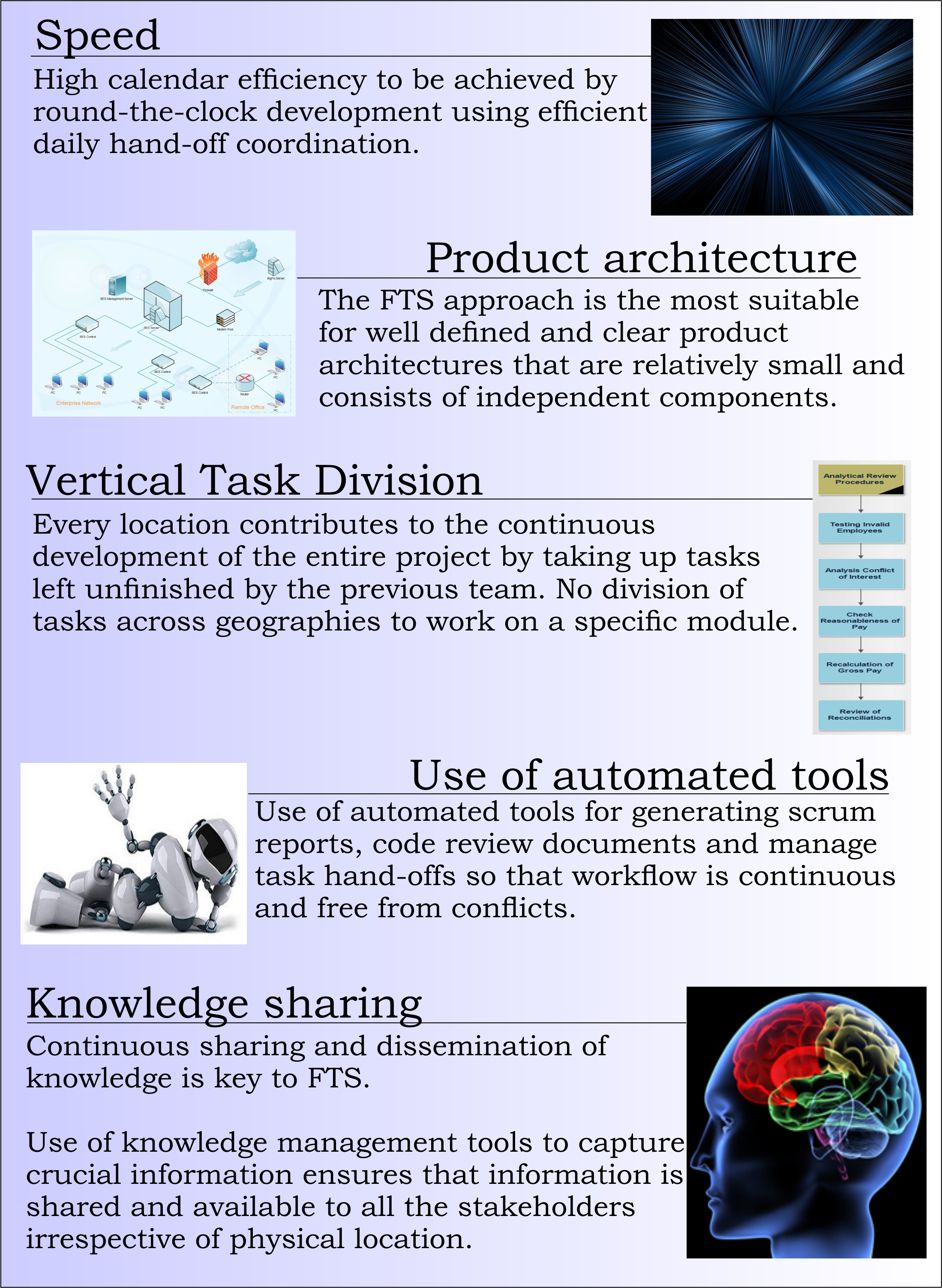

9. Advantages of FTS

The FTS approach utilizes distributed team members spread across time-zones to achieve a single project outcome with the main objective of gaining speed and reducing the time-to-market of a project [13]. This in turn increases productivity. Beside this benefit, there are also other advantages as well which can be found on Fig. 7.

Figure 7: Advantages of the FTS approach

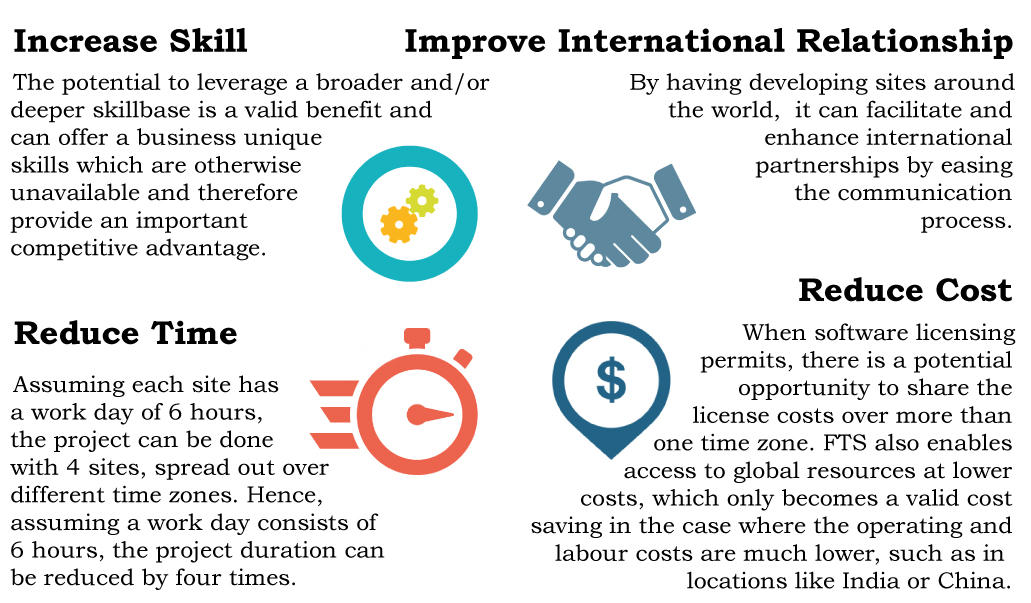

10. Limitations of FTS

FTS has many challenges associated with it and it also faces same challenges of GSD as it is a part of GSD. The success cases in the Industry using FTS are rare, in part due to the lack of well-founded knowledge on applying FTS [9]. The implementation of FTS, if not practiced correctly, may result in failures and projects going over budget [10]. According to Carmel [1], FTS has challenges such as coordination barriers, cultural differences, and communication difficulties depicted in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: FTS limitations and challenges

11. Research Themes

In this section we give a number of research themes within Follow-the-Sun software development research. We identified three main themes, namely challenges and best practices, location selection and hand-offs management. They are summarized in the table below.

| Theme | Description | Research |

|---|---|---|

| Challenges and practices | Research in Follow-the-Sun software development has been done since 1990. Results are generally from case or field studies, resulting in identified challenges and best practices to improve the methodology. | Kroll et al. listed 36 best practices and 17 challenges found in literature [14]. Three categories of challenges were found, namely challenges in coordination (e.g. time zone difference and hand offs management), communication and culture. The top three best practices that were found in research are agile methods, the use of technology for knowledge sharing (e.g. video calls) and process documentation. |

| Location Selection | This theme is specifically for location selection and the impact of it. | This research [15] introduced a routing model, which supports the selection of geographical locations for Follow-the-Sun software development. The research focussed on two aspects: “the optimal time zone difference” and “the natural ease of communication” (i.e. culture and language). There is also research that studied the impact of the number of sites on working speed and accuracy in Follow-the-Sun software development [9]. Overall it was found that increasing the number of sites in a daily cycle increased the working speed. The number of sites had only a small impact on the accuracy. |

| Hand-offs management | Since hand-offs are such an important aspect of Follow-the-Sun software development, recent research studied hand-offs management | Research concluded that nine aspects of management are important for improving hand-offs efficiency [16]: improving communication quality, ensure knowledge transfer between team members and production sites, management of hand-off’s information, developing team’s trust before and along the project, ensure compliance of deadlines, establishing time rules, providing proper technology and tools, delegating responsibility and coordination of task allocation. Since these aspects above are reported to increase efficiency, it was also concluded that when these aspects are taken into account the duration of the project is reduced. |

12. Conclusions

The purpose of this article was to present a comprehensive study on the FTS model for software development. Background, main ideas and principles behind FTS were discussed followed by a brief review on Agile for FTS, advantages and limitations of FTS. One shortcoming of this article is that we have only investigated the effect of FTS on speed, not on the product quality because of lack of suitable documented references.

We have underlined some of the essential concepts of FTS such as use of Agile for FTS, tools required and learnings from past experiences for the efficient implementation of FTS. The FTS model doesn’t seem to be a suitable choice for complete projects, when compared to its applicability for particular phases like - testing where it works very well due to less dependency on hand-off work. This means that efficiency in task hand-off is of paramount importance to the success of the FTS approach. We have discussed how technology tools and infrastructure play an important role in the successful implementation of FTS. Agile seems to be the best and most suitable for FTS based approaches because the principles of Agile anf FTS complement each other. We have also elaborated in depth about the real world examples where FTS was applied. Although there were very less successful cases, some companies still showed positive intent in applying FTS model. Typical challenges such as coordination, communication and culture differences presents a bigger challenge to FTS than GSD, as FTS involves daily hand-offs. There are numerous advantages if the FTS implementation is successful which are reduced time-to-market, reduced software costs, increased international relationships leading to better diversity among companies, etc.

Many companies are looking for efficiency in software development in terms of quality and development time. FTS could provide significant benefit in dealing with these aspects. We have showed earlier that using the concept of calendar efficiency, FTS gives lot of room for decreasing the development time. But in reality not many companies are following this methodology due to a few documented successes and a significant lag in FTS research. A key observation from this study is that even after decade long progress of FTS, its challenges are not overcome yet and it may be relevant to notice that there are no substantial benefits to FTS, thus FTS achievability is an empirical question for which a necessary first step is a consistent definition. To this end, the FTS research needs to be done comprehensively, so that companies start adopting it in real-time projects.

We showed that there are three main research themes, namely challenges and best practices, location selection and hand-offs management. There exist several case and field studies over the years, which resulted in challenges and best practices of FTS. In addition, there is research about location selection and the effect of the number of selected locations. Lastly, we showed that there was a study which researched hand-offs management.

Prashanth G.L, Santosh Malagi, Laurens Van Den Bercken, Ade Setyawan Sajim and Bernd Kreynen are the authors of this blog. In case of any issues with the blog, please contact: guledalprashanth@gmail.com or berd.kreynen@hotmail.com.

13. References

[1] Erran Carmel, J Alberto Espinosa, and Yael Dubinsky. “follow the sun” workflow in global software development. Journal of Management Information Systems, 27(1):17-38, 2010.

[2] Murray R Millson, SP Raj, and David Wilemon. A survey of major approaches for accelerating new product development. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 9(1):53-69, 1992.

[3] Frederick P Brooks Jr. The Mythical Man-Month: Essays on Software Engineering, Anniversary Edition, 2/E. Pearson Education India, 1995.

[4] AGupta, Amar. “Deriving Mutual Benefits from Offshore Outsourcing: The 24-Hour Knowledge Factory Scenario.” (2007).

[5] Amar Gupta. The 24-hour knowledge factory: can it replace the graveyard shift? Computer, 42(1):66-73, 2009.

[6] Carmel, Erran, Yael Dubinsky, and Alberto Espinosa. “Follow the sun software development: New perspectives, conceptual foundation, and exploratory field study.” System Sciences, 2009. HICSS’09. 42nd Hawaii International Conference on. IEEE, 2009.

[7] Monica Yap. Follow the sun: distributed extreme programming development. In Agile Conference, 2005. Proceedings, pages 218{224. IEEE, 2005.

[8] Christian Doerr. Network Security in Theory and Practice. Christian Doerr, Federal Republic of Germany, 2017.

[9] Rini van Solingen and Menno Valkema. The impact of number of sites in a follow the sun setting on the actual and perceived working speed and accuracy: A controlled experiment. In Global Software Engineering (ICGSE), 2010 5th IEEE International Conference on, pages 165–174. IEEE, 2010.

[10] Eoin Ó Conchúir, Helena Holmstrom Olsson, Par J Agerfalk, and Brian Fitzgerald. Global software development: never mind the problems – are there really any benefits? 2006.

[11] Siri-on Setamanit, Wayne Wakeland, and David Raffo. Improving global software development project performance using simulation. In Management of Engineering and Technology, Portland International Center for, pages 2458–2466. IEEE, 2007.

[12] Miguel Jiménez, Mario Piattini, and Aurora Vizcaíno. Challenges and improvements in distributed software development: A systematic review. Advances in Software Engineering, 2009:3, 2009.

[13] Alex Cameron. A novel approach to distributed concurrent software development using a follow-the-sun technique. Unpublished EDS working paper, 2004.

[14] Josiane Kroll, Sajid Ibrahim Hashmi, Ita Richardson, and Jorge LN Audy. A systematic literature review of best practices and challenges in follow-the-sun software development. In Global Software Engineering Workshops (ICGSEW), 2013 IEEE 8th International Conference on, pages 18–23. IEEE, 2013.

[15] Christian Visser and Rini van Solingen. Selecting locations for follow-the-sun software development: Towards a routing model. In Global Software Engineering, 2009. ICGSE 2009. Fourth IEEE International Conference on, pages 185–194. IEEE, 2009.

[16] Josiane Kroll, Ita Richardson, Jorge LN Audy, and Jude Fernandez. Handoffs management in follow-the-sun software projects: a case study. In System Sciences (HICSS), 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on, pages 331–339. IEEE, 2014.

[17] Amar Gupta, Rajdeep Bondade, and Nathan Denny. Software developmentusing the 24-hour knowledge factory paradigm. 2008.

[18] Josiane Kroll, Rafael Prikladnicki, Jorge LN Audy, Erran Carmel, and JudeFernandez. A feasibility study of follow-the-sun software development for gsd projects. 2013.

[19] Treinen, James J., and Susan L. Miller-Frost. “Following the sun: Case studies in global software development.” IBM Systems Journal 45.4 (2006): 773-783.

[20] ZONE, HOW INFOSYS MANAGES TIME. “Quarterly Executive.” (2006).